EJPS 11 Artiga; Shaw; Reydon

Artiga, M. Biological functions and natural selection: a reappraisal. Euro Jnl Phil Sci 11, 54 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-021-00357-6

2-4

- Funções biológicas cumprem o papel de explicação e de normatividade.

- Aborda a Selected-effects etiological theory "according to which the notion of a function can be analyzed in terms of selection for", geralmente com respeito a seleção por SN.

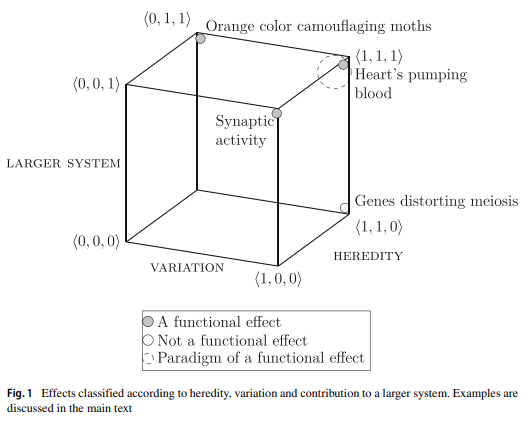

- A partir de T1 e T2 chega a T3, que discutirá:

- T1 A trait T has the function F iff T has been selected for F.

- T has been selected for F iff F was an effect of T and the following conditions hold: heredity; variation; differential reproduction; causation

- T has the function F iff F was an effect of T and the [same] conditions hold

6

- Nem todas as condições precisam ser plenamente atendidas. Atender todas totalmente faz um caso "paradigmático".

- Functions possess two puzzling features, EXPLANATION and NORMATIVITY. Since, according to T3, functions are effects that comply with Variation, Heredity, Differential Reproduction and Causation, the fact that an effect satisfies these requirements should explain why it possesses these two puzzling features. Yet it is much easier to claim that effects that satify T3 exhibit EXPLANATION and NORMATIVITY than giving reasons for this statement. How can we justify this claim?

- The strategy I will follow is to consider each of the conditions included in T3 separately and show how they contribute to explain these two puzzling properties of functions. For instance, I will show that the fact that a trait’s effect E in a population P satisfies heredity contributes to explain why this effect sets a normative standard (i.e. it exhibits NORMATIVITY). In a sense, the strategy is to vindicate the idea that effects that comply with T3 have a specially normative and explanatory role by decomposing T3 and showing how each of the different conditions contributes to account for these two aspects.

- Furthermore, assessing to what extent each condition of T3 (heredity, variation, etc..) contributes to accounting for the two puzzling features of function (EXPLANATION and NORMATIVITY) will be important later on: we will consider some philosophers (e.g. Buller, Garson) who hold that satisfying some conditions of T3 is not required for a trait to have a function. One way of responding to these challenges is to show that each of these conditions makes an important contribution to the explanation of why functions play their distinctive normative and explanatory role. To do that, however, we need to discuss the contribution that some conditions makes on its own to account for NORMATIVITY and EXPLANATION.

7

- Linguagem teleologica designa um processo robusto, isto é, que chega sempre a um mesmo resultado

8

- T3 explica a parte explanation: if, within a population, the process leading to the actual distribution of traits T performing F lacked significant variation in the recent past, then the process might have been highly unrobust, in the sense that a different trait with some slightly different effect F* could have easily done much better and wiped out Ts performing F from the population. In contrast, if, in the recent past, the population included diverse traits with various kinds of effects, then the process leading to the current presence of traits performing F is likely to be more robust. Thus, the existence of variation in a population supports the idea that performing F provides a robust-process explanation of the persistence of a certain trait within this population

10

- Add um novo critério a T3, que passa a ser T3+. "o efeito deve ter contribuido para o fitness de um sistema maior."

14

"notice that failing to possess some properties may leadan effect to qualify as marginal, whereas lacking others entaisl not having a function at all"

16- Difere seleção para e seleção de "s selection for warmth, but only selection of thickness".

17

- Casos de seleção paradigmáticos satisfazem os critérios de Variasção e Hereditabilidade, mas casos marginais podem não satisfazer o segundo.

18

First, I argued that T3 should probably be supplemented with a fourth condition,

namely that a trait should contribute to the fitness of a larger system (what I called

‘T3+’). The main motivation is to provide a theory that be able to account for the two

main features of functions (EXPLANATION and NORMATIVITY) and address some

counterexamples. Secondly, I argued that T2 and T3+ should primarily be understood as establishing what is required for an effect to be a paradigm case of selection

for and function, respectively. Hence, although prototypical instances of function and

selection for must satisfy all of these conditions, marginal cases might fail to comply with some of them. Thirdly, some of the conditions in T2 and T3+ are necessary

conditions for being an instance of function or selection for. For example, no entity

that fails to comply with Contribution to a Larger System can be said to have a function (not even marginally) and no effect that fails to fulfill Variation can be said to

have been selected for. I also argued that this perspective can accommodate some

alleged counterexamples that have been raised against the standard analyses of these

two notions. Additionally, I contended that on this interpretation, the process that

gives rise to functions only partly overlaps with the selection process involved in natural selection. In other words, some of the dimensions that are relevant for attributing

one property are also relevant for attributing the other, but not all of them. Thus, T1

should be abandoned. This might be partly due to the different explanatory goals of

a theory of natural selection and a theory of function.

Finally, I suggested that this perspective is fully compatible with a naturalistic theory of function, since it only undermines the simplistic view that seeks to reduce one

property to the other. The door is still open for an approach that explains functions

in terms of a causal process from the recent past that approximates natural selection

in various respects. Thus, the results of this paper vindicate an etiological account

of function, albeit one that must differ in some respects from the Selected-Effects

Etiological Theory.

--------------Shaw, J. Feyerabend, funding, and the freedom of science: the case of traditional Chinese medicine. Euro Jnl Phil Sci 11, 37 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-021-00361-w [OA]

- Feyerabend e defesa pela não liberdade da ciêrncia. que deve ser monitorada democraticamente

- Scientifc chauvinism refers to the phenomena where a set of practices (Western medicine in this case) is labeled ‘scientifc’ and, when combined with the presumption that non-science is somehow problematic, leads to the elimination of conficting practices. Scientifc chauvinism is anti-pluralist since it tries to eliminate research and, as anyone familiar with Feyerabend will know, is therefore unwarranted 5

- Comparação entre tcm e lysenko: Feyerabend locates the problematic aspects of the Lysenko affair with the totalitarian means by which the Soviet state interfered in the development of genetics: Considering the sizeable chauvinism of the scientifc establishment we can say: the more Lysenko afairs the better (it is not the interference of the state that is objectionable in the case of Lysenko, but the totalitarian interference which kills the opponent rather than just neglecting his advice) (Feyerabend, 1975a, 7). 7

- Feyerabend even claims that democratic supervision is justifed even if it makes for worse science (87). These rights follow from his notion of freedom. To live a free life, individuals must have resources to help them live the life they want – knowledge is one such resource. Thus, citizens have a positive right to knowledge. According to Feyerabend, this right entails that citizens should be allowed to have an active role in determining what knowledge should be produced and how. Result: science should produce the right kinds of knowledge where the ‘right kinds’ is to be determined democratically [...] Feyerabend argues as though there is no contradiction between the arguments from pluralism and democracy, but clearly there is: citizens may be scientifc chauvinists and reinforce monism in their preferred direction. Similarly, citizens may become dogmatically anti-scientifc and attempt to censor scientifc research in an anti-pluralist fashion. Doing so would be perfectly within their rights. In these cases, the external interference Feyerabend promotes would scarcely difer from the totalitarian measures taken by state ofcials trying to promote their own agenda. Remember that totalitarian interference, for Feyerabend, is understood as the enforcement of monism. He presumes that the general public will not do this – but this presumption is not always going to hold. As his hero, J.S. Mill, pointed out: a tyranny of the majority is tyranny, nonetheless. In these cases, Feyerabend objects to the freedom of science on incompatible grounds since the goals of increasing pluralism can confict with the rights of citizens in a free society. Feyerabend never notices or addresses this tension directly. 10

- [...] science should only be democratically supervised in cases where we have a sufciently mature citizen base [Feyerabend]. [Na nota o autor critica o idealismo politico de Feyerabend] 12

- O autor faz uma distinção entre supervisão e participação, a primeira aponta uma relação de poder assimétrica enquanto a segunda não. Assim, a partir de um raciocíno lógico baseado nas ideias de F, chega a: Democratic supervision is warranted in cases of urgent science. Democratic participation is warranted in cases of luxury science and some cases of urgent science. 14

- Once we understand this [that scientists are not an isolated body for Polanyi], we can see the dimensions of critical discourse Polanyi celebrates and those he suspects. Critical interaction between agents, for Polanyi, should be between agents with the appropriate tacit knowledge. Scientists are free to criticize other scientists on whatever they see ft. But ‘criticisms’13 from outsiders are only worth taking seriously if scientists see some merit in them. If Trump criticizes anti-malarial research, his criticism only gets uptake if practicing scientists see merit in Trump’s claims. This transformation from criticism to a criticism worth considering is done by recognizing the ‘interest’ intrinsic to the fnding and can connect it with existing bodies of scientifc knowledge (Polanyi, 1940, 4–8). To do this, the inquirer requires familiarity with extant science and how outside knowledge may advance it. The outsider ‘criticism’ is only valuable if they can be attached to existing scientifc knowledge.14 Thus the source of the criticism is from the outside, but it is only a criticism because scientists construct it as such. Outsiders can criticize all they want but for that criticism to genuinely contribute to the growth of science, it must be recognized as having some value and this can only be done by knowing the science. Since knowing is tacit, recognizing those criticisms that are worth taking seriously is within the purview of scientists even if the source of that criticism came from some crank. 17 [muito interessante!]

- Feyerabend propoe uma supervisão top down por parte dos leigos; polanyi o contrário.

- Visão de feyerabend: The scientists ‘tacit knowledge’ psychologically derived from scientifc chauvinism which, upon refection, is a bad argument. This was revealed through outside interference in science. This is in stark contrast to Polanyi’s view where, after a criticism of the basic ideology of science has been leveled, science “must then be defended on its true grounds. I suggest that for this purpose our beliefs, including our belief in science, will have to be declared explicitly, in fduciary terms” (Polanyi, 1952, 232). For Feyerabend, science is not intrinsically deserving of any trust and need not be refexively defended from outsiders. It is only trustworthy after it has survived criticism. 17-8

- The shallowness of Feyerabend’s social commentary reveals a common tendency that he berated: applying highly abstract arguments to concrete situations without considering the details of the particular case. Indeed, the devil is often in the details entailing that a deep analysis may reveal that Feyerabend’s argument for the Bauman amendment may be counterproductive to its own goals. [...] While this seems obvious, it is a mistake philosophers and social commentators, Feyerabend included, often make: practical advice cannot come from highly abstract refections about the nature of science and its place in society alone. Philosophical proclamations about the place of science in society depend on (often) hidden empirical premises that must be evaluated using detailed studies of particular contexts. Feyerabend’s mistake, then, provides a lesson for all of us – a lesson some are still struggling to learn (see Fehr & Plaisance, 2010). Indeed, too many papers and books speak about ‘the’ freedom of science as if this was a tangible viewpoint one could reasonably hold. 21-2

VER

Preston, J. (1997). Feyerabend’sPolanyian turns. Appraisal, 1, 30–36.

Sismondo, S. (2011). Bourdieu’s rationalist science of science: Some promises and limitations. Cultural

Sociology, 5(1), 83–97

Fehr, C., & Plaisance, K. (2010). Socially relevant philosophy of science: An introduction. Synthese,

177(3), 301–316

Wilholt, T., & Glimell, H. (2011). Conditions of science: The three-way tension of freedom, accountability and utility. In M. Carrier & A. Nordmann (Eds.), Science in the Context of Application. (pp.

351–370). Springer

Polanyi, várias refs sobre sua filo da ciência

----------

Reydon, T.A.C. Misconceptions, conceptual pluralism, and conceptual toolkits: bringing the philosophy of science to the teaching of evolution. Euro Jnl Phil Sci 11, 48 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13194-021-00363-8 [OA]

- Ensino por mudança de conceito. Mudança dos préconceitos em vez de aquisção em situação de tabula rasa. O préconceito ou conceito alternativo dever ficar explícito para que o aluno possa mudá-lo de modo a se tornar o cnceito científico aceito.

- Widespread misconceptions pertain to the origins of mutations (where mutations are often seen as induced rather than spontaneously occurring), the failure to appreciate the probabilistic nature of Darwinian evolution, views of adaptive change as guided by the needs of organisms to survive, the failure to distinguish between the development of organisms and the evolution of populations (the view that individual organisms adapt rather than seeing that adaptation is a population-level process), anthropomorphic conceptions of selection as performed by a selecting agent, and more. 5

- sobre fitness: Views that ‘ftness’ means physical strength; The view that natural selection causes only the very fttest organisms to survive; The view that individual organisms can change to better ft into their environments; The view that ftness is a property of species rather than organisms, in the sense that the fttest species prevail; The view that the term ‘ftness’ applied to genes means that an allele is dominant, as opposed to recessive 5-6

- These debates show one thing particularly clearly: neither for the concept of natural selection nor for the concept of ftness clear target concepts in biological science exist. For the concept of ftness, there isn’t even clarity regarding the number of different ftness concepts, their relations to each other, or their usefulness in biological research. Note that the concept of ftness is not special in this respect, but rather an instance of a common state of afairs in the sciences. Historians and philosophers of science (and in particular of biology) have come to endorse pluralism regarding many central scientifc concepts – in biology for instance with respect to the concepts of species, gene, function, ftness, individual, and others (see, prominently, Dupré, 1993). Indeed, “[i]t is only a slight exaggeration to say that conceptual pluralism is taking over debates in (philosophy of) science” (Taylor & Vickers, 2017: 17). Conceptual pluralism as a stance in the history and philosophy of science amounts to acknowledging that it cannot be generally expected that there are uniquely correct meanings for central concepts in the sciences. Technical scientifc terms often have related but diferent meanings in diferent contexts of scientifc research and it is not uncommon for diferent meanings to be used in parallel to serve diferent purposes in diferent contexts of research (Taylor & Vickers, 2017: 17–18; Kampourakis, 2018). In addition, for many concepts there are ongoing, open-ended debates about their meanings, with participants in the debates fnding themselves unable to fnd clear ways to adjudicate between competing interpretations 7

- Conceitos de fitness: Darwian or ecological fitness (applied to organisms or types); individual actual fitness; average actual fitness; propensity interpretation; inclusive fitness.

- toolkit: set of concepts and conceptions available to students, teachers and researchers to work with in their learning, teaching and research practices 11

- The natural phenomenon that is investigated using the term ‘ftness’ thus constitutes a unifying theme for the concept. It can be used to show why biology came to have a multitude of ftness concepts: biologists were (and still are) searching for good tools to study this natural phenomenon, and the various concepts associated with the term ‘ftness’ are such tools. The various concepts in the slots of the toolkit can thus be assessed with respect to their usefulness for their specifc task in the investigation of this natural phenomenon. Conceiving of the term ‘ftness’ as referring to a conceptual toolkit and the debate as being about the usefulness of the various tools in the toolkit, I suggest, provides a more adequate picture of actual biological science than thinking of ‘ftness’ as a unifed scientifc concept 16

- the history of scientifc concepts often is a history of intense debate, and conceptual pluralism is not a sign of deep confusion in an area of science but rather sign of good science. Consider the debate that followed the criticism of inclusive ftness theory by Nowak et al. (2010): not only is this a case of open debate among a considerable part of the relevant scientifc community, it also is a case of an eminent member of the community (E.O. Wilson) changing his view on a particular part of scientifc subject matter. Indeed, the history of ftness concepts is one long debate about the usefulness of various defnitions, and the ftness debate can help to show how theoretical debates, changes of opinion and (occasionally heated) criticism are crucial elements of good science. 17

Comentários

Postar um comentário