HPLS 43 Jímenez-Pazos; Winsor; Witteveen.

Jiménez-Pazos, B. Darwin’s perception of nature and the question of disenchantment: a semantic analysis across the six editions of On the Origin of Species. HPLS 43, 57 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-021-00373-y [OA]

- The ideas just described then point to a contradiction that allows the formulation of questions that will mark the argumentative development of this article. If Darwinian science,—whether it is an over-dedication to scientifc study, or perhaps the internalization of a supposedly pessimistically disenchanting message found in OS—, is the cause, according to Darwin, of the atrophy of the part of his brain dedicated to artistic appreciation, and also of the inability to experience feelings of aesthetic exaltation in nature, why does Darwin end OS, one of the most outstanding works in the history of science that would have contributed to disenchantment, with a message that indicates intellectual and aesthetic fascination? Is disenchantment compatible with aesthetic experience and sensibility for natural beauty? Considering that the OS text varied considerably over the years, leading to diferent editions with multiple additions and deletions, would it be possible to detect in the lexical-argumentative evolution of the different editions of OS signals that anticipate a late disenchantment in Darwin? Is it his disenchanted conception of the world that led Darwin to believe himself colour blind in the face of the beauty of nature? Was Darwin disenchanted at the end of his life, or just confused by his inexplicable lack of aesthetic and artistic interest? I will answer these questions in four chapters dedicated to unravelling the characteristics of Darwin’s perception of natural beauty.

- Desencatemento derivado de Weber em seu Science as a vocation (1918), em suma significa a materialização do mundo. A autora equaliza com secularização, desacralização ou naturalização científica.

- Há uma visão contrária que afirma que o estudo natural re-encanta o mundo por possiblitar uma compreensão mais profunda da natureza.

- Although recent studies (Mahmoudi and Abbasalizadeh 2019) have argued in favour of the enriching approach that statistics and text mining strategies can ofer to literary studies, other pieces of research (Da 2019) warn us about the problems, logical fallacies and conceptual faws that could arise in computational literary studies. nota 11 9

- To carry out an analysis of the Darwinian lexicon through the six editions of OS I have had to computationally process the vocabulary contained in these editions using both manual text-editing and text-mining strategies, and WordSmith Tools (Scott 2020), a software package for linguistic corpus analysis. To do this, frstly, since WordSmith Tools only processes fles in txt format, I have taken as reference the textual versions of the six editions of OS available at http://darwin-online.org. uk (van Wyhe 2002) and, following manual text-editing strategies—these include, for instance, eliminating special characters the software package does not properly process, or reducing the length of the texts by eliminating the space between paragraphs—, I have thoroughly prepared the texts to create six documents, each corresponding to the six editions of OS, in txt format. Secondly, I have processed these six documents with the WordList tool in WordSmith Tools to extract word frequency lists, which contain all the lexical material of the six editions of OS; in this type of lists, words occurring in the texts are ordered by their frequency of occurrence, from the most commonly occurring words down to those words that appear less frequently. Thirdly, after an in-depth scrutiny of all the words included in the six word frequency lists, I have selected the key adjectives and adverbs that are relevant to this study—such as the ones which meet the conditions just described in points 1, 2, 3 and 4—. Finally, I have manually analysed these words, one by one, in each of the six txt fles, in order to, frst, know which nouns and verbs they afect and, second, detect word additions, deletions or lexical variations that Darwin might have applied to the diferent OS editions. I am aware of the miscalculations that can be made in a manual, not automated lexicon scrutiny. Therefore, to guarantee the exhaustiveness of my analysis on occurrences and lexical variability, I have complemented my manual text-mining strategies with the use of the Concord tool in WordSmith Tools, useful to locate all the occurrences of a specifc word in their textual context.

- The fact that in a work like OS the adjective beautiful has a considerable lexical presence that increases throughout the editions—this is confrmed by the fact that there is a terminological increase of more than twice as many occurrences from the frst edition of OS to the sixth—, not only allows us to confrm that Darwin’s aesthetic interest increases in line with his growing scientifc knowledge of nature, but points out that Darwin does not want to dispense with descriptions that show his aesthetic and emotional appreciation of the objects of study. Why would Darwin need to include his aesthetic-emotional assessment of the mechanisms and processes that he explains, if not to assert his aesthetic and intellectual fascination? 13

- In brief, as advanced above, since Darwin does not use any of the religious or spiritual adjectives as argumentative foundation for his explanations in OS, it is therefore possible to conclude that disenchantment also manifests itself in the texts in the form of the absence of religious or spiritual adjectives with relevant theoretical value. 19

22

So, if the supernatural turns out to be the only resource that can account for what

has been experienced in the face of majestic scenes of nature capable of generating

a feeling of sublimity, and Darwin alludes to an irremediable supposed loss of faith

over time, it is understandable that he claimes to sufer a type of colour blindness, a

defective perception before the sublime scenarios of nature. It is, however, striking

that Darwin did not later clarify that what is truly defective, that is, the cause of the

sensation of colour blindness, is the missing religious link of the triad 1. Perception

of the beauty of nature; 2. Religious feeling; 3. Experimentation of the sublime, and

not the ability to perceive beauty.

I therefore deduce the existence of two types of perceptual losses—that are not

opposed, but overlapping—that will allow us to devise a solution to Darwin’s problem. First, the loss referring to cerebral atrophy, erroneously, in my view, attributed

to an over-dedication to scientifc activity. Second, the loss produced by disenchantment, in an emotionally negative sense, with respect to the landscape aesthetic

perception, that is, a supposed colour blindness derived from the loss of religious

beliefs; this loss of aesthetic perception caused by disenchantment, should, nevertheless, have been specifed as a modifcation of perception, and not as a loss.

The error of Darwin’s interpretation could be of a syllogistic nature. His mind

seems to operate as follows: (a) There is aesthetic experience if—in nature or art—

the contents XYZ are perceived; (b) I do not perceive them anymore; (c) Then, I no

longer have aesthetic sensibility. However, premise (a) is arbitrary, something that

Darwin, due to cultural or personal reasons, perhaps, could not notice.

This syllogistic deduction could have led Darwin to believe that, similarly, he has

lost the taste for the higher aesthetic tastes. If Darwin identifes the sublime with

transcendence, with the imprint of divinity in nature, and he ceases to establish such

a relationship, given the ideological demands consequence of the assimilation of his

theory of evolution, it is therefore plausible to accept that he believed to have lost, at

the same time, the feeling for the higher aesthetic tastes—linked to arts which could

equally have led Darwin to experience feelings of religious exaltation—and for certain aspects of the natural beauty that he could initially perceive. It is then possible

to believe that both feelings of loss have a common root: the profound change that

his scientifc theory causes to his worldview, namely, the alteration and destruction

of many of the basic assumptions of the pre-Darwinian worldview.

In sum, not only the colour blindness passage, but also that of cerebral atrophy

could be related to the loss of perception of the supernatural in nature. This could

have caused Darwin the feeling of having lost aesthetic sensibility.

23

In sum, as can be inferred from the semantic analysis of the lexical results,

despite Darwin’s conception of the world is supported by disenchanted ontological

pillars, his view of nature has not been aesthetically weakened.

Secondly, in regard to the question about whether it was the disenchanted conception of the world that led Darwin to believe himself colour blind in the face of natural beauty, it is possible to confrm that the type of disenchantment Darwin describes

in AB, that is, the cessation of religious belief, apparently brings him closer to the

concept of disenchantment, suggested by Weber, that has a negative connotation:

“atrophy” and “colour-blindness” are not terms compatible with a complete, intense

and positively disenchanted aesthetic perception of the landscape, or more specifcally, with the aesthetically and scientifcally inspiring view of the world proposed

by Darwin, as evoked in the concluding lines of OS.

However, it is not possible to infer this negatively disenchanted view from the

study of the lexical evolution of the diferent editions of OS, because, as has been

demonstrated, the variations of the Darwinian lexicon show a growing fascination,

above all, for constitutive, essential aspects of nature. So, we could state, at least

tentatively, that Darwin could perhaps have confused his feelings of an inexplicable

lack of interest in landscape aesthetics and the arts. Given the correlation between

perception, in nature, of beauty, of the sublime in it, and of the feeling of the supernatural, inferred through the commemoration of the passage from the Journal of

Researches which reveals the conviction that there is something more in man than

the mere breath of his body, the loss of religious feeling, in conjunction with the

detection of an atrophy with respect to the fnest arts, could have driven Darwin

to deduce, perhaps wrongly, a loss of the ability in aesthetic perception in general,

instead of considering it to be a modifcation of perception.

In short, the cause of Darwin’s error of interpretation of his aesthetic sensibility

would then have been to assume the equation of equality between aesthetic sensibility in the face of nature and the perception of its beauty as part of the vestigia Dei.

VER

Schweber, S. S. (1977). The origin of the “Origin” revisited. Journal of the History of Biology, 10(2),

229–316.

Liepman, H. P. (1981). The six editions of the origin of species: A comparative study. Acta Biotheoretica,

30(3), 199–214

------------------------

Winsor, M.P. “I would sooner die than give up”: Huxley and Darwin's deep disagreement. HPLS 43, 53 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-021-00409-3 [oa]

- Não há uma identificação tão estreita entre classificação e evolução.

- Darwin discutiu com Huxley sobre isso.

- No trabalho com os cirripedes se deparou com dificuldades de classificação

- Early naturalists who catalogued forms of life had struggled with the question of continuity: when all the world’s living things have been found, would nature be continuous, because transitional forms will fll in the gaps we now see? That would expose taxonomic categories as human inventions. Or will nature still be discontinuous, in which case natural groups will be confrmed as real entities? (Stevens, 1994). Darwin collapsed that longstanding dichotomy. In his vision of the history of life, the discontinuity seen today is real, and continuity is also real but is located in the past, where an unbroken stream of life stretches back countless millions of years, leaving us only a few remnants as fossils. What we call a taxonomic group is a collection of species that are literally kin. Species in a genus have a close blood relationship while species in a higher group are also related by blood, but the line of connection reaches even further into the past. M. P. Winsor 1 3 53 Page 6 of 36 This was a version of evolution which few of his contemporaries had yet imagined. It means that classifcation must be both natural and man-made at the same time.8 It is impossible to chop groups out of a continous stream without making arbitrary choices. Darwin envisioned the forces of change as irregular, so that species today have irregular degrees of relatedness. The fact that taxonomists struggled to defne species was to Darwin not a problem but a clue. Many species are easy to distinguish, while other species elude defnition, and this to him was evidence that for some species, a process of change is going on now, while for other species, change happened in the past. Groups above the level of species were grist for his mill in the same way. The fact that eminent taxonomists could disagree about the higher groups, Darwin took as evidence for his theory 5-6

- I for one believe that a Scientifc & logical Zoology & Botany are not at present possible— for they must be based on sound Morphology— a Science which has as yet to be created out of the old Comparative Anatomy — & the new study of Development [embryology] When the mode of thought & speculation of Oken & Geofroy S. Hilaire & their servile follower Owen, have been replaced by the principle so long ago inculcated by Caspar Wolf & Von Baer & Rathke— & so completely ignored in this country & in France up to the last ten years— we shall have in the course of a generation a science of Morphology & then a Scientifc Zoology & Botany will fow from it as Corollaries— Your pedigree business is a part of Physiology— a most important and valuable part— and in itself a matter of profound interest— but to my mind it has no more to do with pure Zoology— than human pedigree has with the Census— Zoological classifcation is a Census of the animal world (Burkhardt & Smith, 1990, 6: 461–462) 6-7

- . Although Darwin made the strategic decision not to deal with our own species in the Origin, this sentence exposes the fact that human races had always been for him good examples of variation within a species. He deleted the sentence [about negroes 1859, 424) in the 1869 edition of the Origin. 9

- r. Huxley’s odd supposition (what if we knew nothing about life?) refected two categories of study: anatomy deals with structure and physiology deals with function. This helps us understand what Huxley meant in his census letter. Darwin’s pedigree business belonged to physiology because reproduction is a vital function of living things. For Huxley, classifcation should only consider the features of dead specimens. 12

- In the Origin Darwin asks his readers to imagine that an ancestral species of bear has given rise to several descendant species, and that in addition to giving rise to several new kinds of bears, one line of its descendants has gradually evolved into a kangaroo. This strange conjecture concludes a paragraph that began by arguing that naturalists already prefer genealogy over appearance when they classify males and females together into one species. He wanted his readers to extend that principle above the species level up to higher groups: genera and families. 13

- Sticking to his assignment, Huxley used examples from physiology, such as the circulation of blood, saying little about either morphology or natural history. With the same rhetorical energy that later made him such a powerful supporter of evolution, Huxley set out to elevate the status of biology. How wrong it is to call biology an “inexact science,” he maintained, as if it were inferior to the “exact sciences” (physics, chemistry, and mathematics). By no means! Its methods “are obviously identical with those of all other sciences.” And so are its results. 17

- Analogia em classificação e homologia em morfologia.

- Questão com strickland e owen, mas: Most naturalists continued to think of afnity as a relationship between groups, reserving homology for the correspondence of parts of organisms, just as Owen had done. 23

- . In this impressive work, Whewell gave an accurate and clear account of the fact that Linnaeus considered his higher groups (class and order) to be artifcial and his lower groups (genus and species) natural. Whewell explained that Linnaeus had hoped that in the future his artifcial groups would be replaced by natural ones, and Whewell celebrated the fact that botanists like Alphonse de Candolle and zoologists like Cuvier were working toward that end. Naturalists recognized natural groups, Whewell said, by using a sort of “latent instinct.” 23

- Naturalists do not work from a list of characters, he said; what they do is compare a newly discovered form to a known one 24

- Mill quoted at length Whewell’s assertion that zoologists and botanists were right not to defne kinds of animals and plants, and then proceeded to contradict him. It is certainly difcult, Mill admitted, to identify all the characters by which we recognize a living kind, and the method of comparing things to a type is often useful; nevertheless, he insisted, a scientifc naturalist ought to discover and enumerate characters with which to defne a natural group. 24

- Huxley was insisting that biological groups were governed by defnition rather than by types 25

- O molusco ancestral da aula de zoologia surgiu com Huxley, mas representa um arquétipo não um ancestral. Ver lindberg e Ghiselin 2003

- It is one thing to believe that certain natural groups have one defnite archetype or primitive form upon which they are all modelled; another, to imagine that there exist any transitional forms between them. Every one knows that Birds and Fishes are modifcations of the one vertebrate archetype; no one believes that there are any transitional forms between Birds and Fishes. (1853a, pp. 62n–63n) 27

- By the Common Plan or Archetype of a group of animals we understand nothing more than a diagram, embodying all the organs and parts which are found in the group, in such a relative position as they would have, if none had attained an excessive development. It is, in fact, simply a contrivance for rendering more distinctly comprehensible the most general propositions which can be enunciated with regard to the group, and has the same relation to such propositions as the diagrams of a work on mechanics have to actual machinery, or those of a geometrical work to actual lines and fgures. We are particularly desirous to indicate the sense in which such phrases as Archetype and Common Plan are here used; as a very injurious realism— a sort of notion that an Archetype is itself an entity— appears to have made its way into more than one valuable anatomical work. It is for this reason that if the term Archetype had not so high authority for its use, we should prefer the phrase ’Common Plan’ as less likely to mislead. ([Huxley], 1855, p. 856) 28-9

- The story of Huxley’s public defence of evolution is one of the best known in the history of science. Instead of claiming that Darwin was right, he made the issue about protecting science from religious control. With respect to evolution, Huxley’s ideas difered from Darwin’s in a number of signifcant ways: he was lukewarm about natural selection and he held that the origin of species lacked experimental proof. Although he stopped using the word archetype, Huxley never abandoned the metaphor of plan. Nor did he ever change his view of what is wanted in proper science: that facts of structure should be recorded independent of theory (Lyons, 1995; Richmond, 2000; Winsor, 1985). Huxley’s words probably had at least as much infuence on nineteenth century biology as anything Darwin wrote, not only because of the wide readership of Huxley’s essays, but because of his infuence on education. His introductory textbooks, and those written by his students, presented facts of physiology and anatomy as faits accomplis, and mostly ignored evolution. Darwin never claimed that classifcation must be based upon evolution, because he knew that before 1859 taxonomists had made good progress toward discovering the natural system. He simply expected that people who believe in evolution would naturally prefer taxonomic groups to express genealogy whenever genealogy can be inferred. By 1868 Huxley came to agree with this (DiGregorio 1984, p. 78). 31-2

- Patter cladistics ainda é um exemplo de separação de evolução e classificação.

ver

Magnus, P. D. (2015). John Stuart Mill on taxonomy and natural kinds. HOPOS: The Journal of the

International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science, 5(2), 269–280.

McOuat, G. R. (1996). Species, rules and meaning: The politics of language and the ends of defnitions in 19th century natural history. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science, 27(4),

473–519.

McOuat, G. R. (2009). The origins of natural kinds: Keeping “essentialism” at bay in the Age of

Reform. Intellectual History Review, 19(2), 211–230.

--------------------------

Witteveen, J. Taxon names and varieties of reference. HPLS 43, 78 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40656-021-00432-4

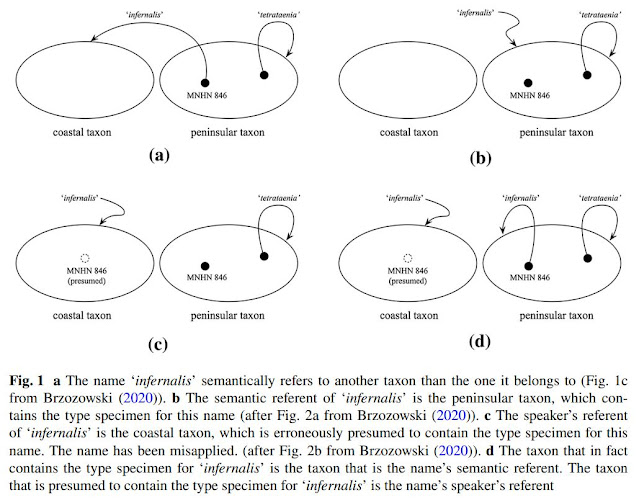

- Linnaean-style, rank-based codes of taxonomic nomenclature provide stability to the relation between taxon names and their referents through the device of nomenclatural types. A ‘type’ in this sense is a member of a taxon that is ostensively designated as the bearer of the taxon’s name.1 When hypotheses about the boundaries of taxa change, types ensure that the relation between taxon names and their referents doesn’t become muddled. 2

- (DD [DE DICTO]) Necessarily, any (sub)species with a type specimen contains its type specimen.

- (DR [DE RE]) Any (sub)species with a type specimen necessarily contains its type specimen

- Argumento original: DD verdadeira, DR falsa. Haber diz DD falsa. Brzozowski defende Haber. Witteveen não.

- “sees a strict relation between misidentifcation of the type specimen and misapplication of a species’ name” ([Harber] p. 12). 4

- However, it is Brzozowski who is misreading Haber here. While it is true that Haber associates the notion of misapplication with misidentifcation in general, Brzozowski overlooks that Haber does not closely associate a misapplication with the misidentifcation of a type specimen. Indeed, Brzozowski fails to notice an important feature of Haber’s account, to wit, the distinction between discovering a misidentifcation and determining its locus. According to Haber, the discovery that a name has been misapplied implies that a misidentifcation of some kind must have occurred, and raises the question which specimens have been misidentifed: “Discovering and resolving a misidentifcation requires identifying which specimens have been misidentifed” (Haber, 2012, 779). In Haber’s view, there is a default mode of resolving a misapplication that can be departed from under certain circumstances. By default, the locus of the misidentifcation is placed on specimens other than the type specimen, but “in some cases misidentifcation may be attributed to the type specimen, triggering (by active petition against the default) the designation of a neotype to serve as the name-bearer of that species” (Haber, 2012, 779). He believes that this is what happened in the case of the Garter snakes that he brought up. In this case, the misidentifcation was discovered at (t2), but it took until (t4) before the locus of misidentifcation was determined to be the type specimen for ‘infernalis’. 5

- Kripke later elaborated that when the name ‘Jones’ is used in this way, Smith is its speaker’s referent and Jones is its semantic referent (Kripke, 1977). In other words, the name ‘Jones’ can be used by a speaker in certain contexts to talk about a person who isn’t Jones, even if the referent of the linguistic expression ‘Jones’ remains Jones, who received this name by ostension. When we apply this distinction to the case of ‘infernalis’ at (t1), we should say that:

- (1) The subspecifc taxon that in fact contained the type specimen for ‘infernalis’ (i.e., specimen MNHN 846) was its semantic referent. (2) The subspecifc taxon that was thought to contain this type specimen was its speaker’s referent. (3) When B&R discovered that the taxon that was thought to contain the type specimen for ‘infernalis’ did not in fact contain it, they showed that the speaker’s referent of ‘infernalis’ failed to coincide with its semantic referent. 6

- Brzozowski’s DN account takes inspiration from Gareth Evans’s generic account of descriptive names (Evans, 1979; Kanterian, 2009). A classic case of a descriptive name in the philosophy of reference is ‘Neptune’. This name was (putatively) not introduced by ostension through telescopic contact, but by the defnite description “the planet x that, if it exists, accounts for irregularities in the orbit of Uranus”.6 This description specifes the reference conditions of ‘Neptune’; the conditions that need to be satisfed for ‘Neptune’ to have a referent. A striking point about descriptive names is that even if their reference conditions aren’t satisfed, they are still intelligible. If it had turned out that Neptune does not exist, the linguistic expression ‘Neptune’ would still be meaningful because of its descriptive content. [NOTA 6: As so often with the ‘real world’ illustrations that make their way into the canon of analytic philosophy, they have a fimsy basis in reality. Urbain Le Verrier, who had predicted the existence of a transUranian planet, frst suggested the name ‘Neptune’ after having learned of its actual existence. (The British, who made claim to having co-predicted the planet’s position, countered that it should be named ‘Oceanus’.) (Kollerstrom, 2009). What matters for the example above is that ‘Neptune’ could have been introduced prior to telescopic discovery. In the remainder of the text I will therefore follow the legend.] 9

- When taxonomists frst coined the name ‘infernalis’ and tethered it to a specimen, they thereby fxed the relevant taxon that this specimen belongs to as the name’s semantic referent. This means that the criterion of application (CA) that Brzozowski ofers cannot be right. Instead of saying that a typifed name applies to the named taxon “by default”, we should say it applies to the type’s taxon “by defnition”. And if it is a defnitional truth that a type belongs to the taxon that is the referent of the name it bears, then it is a de dicto necessity that typifed taxa contain their type specimens. (DD) is true. 10

- We saw that the main pay-of of the general account of descriptive names is that makes intelligible how names can be referring expressions even if they don’t have referents. If Neptune had turned out not to exist, ‘Neptune’ would still be a referring expression, since this name wasn’t introduced through an ostensive act but by means of a description. In contrast, the account of taxon names that Brzozowski presents does appear to rely on ostensive acts: the designation of particular specimens as nomenclatural types. This suggests that taxon names are attached to particular referents, rather than to reference conditions. When a taxon name is coined and attached to a type specimen, the name refers to the taxon that includes this type. We might be wrong about this being a distinct taxon of a distinct rank—and hence we might be introducing a synonym of some kind—but we cannot be wrong about it including the type specimen for the name. 11

- Brzozowski has helpfully introduced the distinction between a name’s semantic referent and its speaker’s referent into the philosophical discussion about the relation between taxon names, types, and taxa. However, I have shown that the correct application of this distinction undercuts Brzozowski’s own two arguments against the thesis that typifed taxa contain their type specimens with de dicto necessity. His frst argument pertains to the fact that semantic and speaker’s reference can come apart when a type specimen is misidentifed. His second argument pertains to the possibility of forcing the semantic referent to realign with the speaker’s referent through an act of neotypifcation. I have argued that neither of these possibilities entail that type specimens can fail to belong to the taxa for which they serve as name-bearers. For such a failure to obtain, it would have to be shown that a type specimen can belong to a diferent taxon than that which is the semantic referent of the name it typifes. Yet, as the distinction between semantic and speaker’s reference helps to show, the semantic referent of a name is defned as that taxon which the type for that name belongs to. Thus, it cannot possibly be the case that a type specimen belongs to a diferent taxon than that which is the semantic referent of the name it typifes. 11

Comentários

Postar um comentário