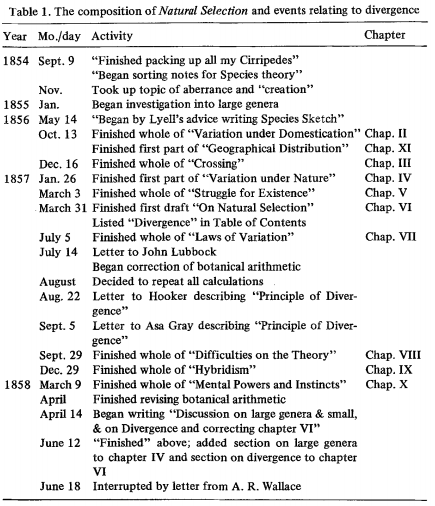

Browne 1980

·

he barely referred to his

botanical statistics or the long sequence of calculations which he had

undertaken from 1854 to 1858. He compressed and simplified these into a few

meager paragraphs, giving his readers only six pages of statistical data to

fill out the discussion of "variation under nature" in Chapter 11.2

By contrast, he had originally devoted over fifty tightly written folios, with

further supplementary notes and tables, to the same theme in the "big

species book," Natural Selection 53

·

botanical arithmetic (a term

coined by Humboldt in 1815)7 consisted merely of counting up all the species in

area A and all those in area B, and itemizing how many were held in common. 55

·

Depois Brown tornou popular o

calculo da media de sps por genero 56

·

the "Sketch" and

"Essay" he had asserted that very little variation was seen in a

"wild state," and had repeated over and over again that "most

organic beings in a state of nature vary exceedingly little."' 8

Consequently, he had relied on geological and geographical changes, either

directly or indirectly (the latter by stimulating a reassociation of

individuals into different patterns), to "unsettle the constitution"

of wild animals and plants. These "unsettling" agents were presumed

analogous to the supposed effects of domestication on the reproductive systems

of organisms under any sort of cultivation. Now, however, by 1854, he was

convinced that organisms in their natural state really did vary without any

such "unsettling" forces. Such a discovery weakened Darwin's

arguments as put forward in the "Essay" where he drew a close analogy

between selection in the wild and under domestication. A change in circumstances

in both cases was assumed to lead to a "certain plasticity of form,"

and the reproductive system was stimulated to produce variant offspring upon

which the selective forces operated. The crucial link was that variants, in

this scheme, arose only when the reproductive system was disturbed. When armed

with the knowledge that varieties pop up in the wild with no reason for their

origination, Darwin saw that the central analogy of his thesis was invalid [After

he “began sorting notes” in 1854] he took up the problem of how a

superabundance of variation in the wild bore on his previous statements about

the origination of species, and how speciation and extinction occurred when

there were no geological or geographical changes necessarily invoked by the

theory. Why, if there was a great deal of variation in nature, did species

become extinct? Surely their variability ought to permit modifications to suit

changing environments. Reopening the question of extinction, he moved to study

forms which vividly represented a past history of extinguishing action. He took

up the topic of aberrance 59

·

It was, he thought, the size of

a genus which made it appear to be aberrant […] So the aberrant groups were, in

his eyes, plainly experiencing an extinguishing force that was removing

species, one by one, from what must have once been a "normal" healthy

complement of species. Despite any variability which aberrant forms may show in

their structure, he concluded, they must eventually become extinct. 60-1

·

Gestalt, se grupos pequenos se

extinguem grupos maiores com formas variants aumentam. 61 Mecanismos de unsettling

e isolamento geográfico não eram mais necessários 62. A mudança seria explicada

pela pangense e cross fertilization

·

1855-7 varieties as little

species: if there were many variations in wild organisms (as the barnacle work

showed to be the case) then there ought to be many varieties; if there were

varieties, then he could expect to fid some that were more strongly differentiated

from the parent that constituted "incipient" species; and one step

further on, he might also expect to find pairs or triplets of closely allied

species which were neither varieties nor fully fledged species, but were

somewhere in between. 63

·

Yet working through his floras,

following the example of Candolle, Darwin confirmed a slight but consistent

tendency for the two characters of a great geographical range and a

multiplicity of individuals to appear in the larger genera 64

·

Darwin made immediate use of

these results in his chapter on geographical distribution for Natural

Selection, composed during the earlier part of 1856 and revised occasionally

thereafter to include new information […] Under the conviction that it was the

big groups in nature that were more widely spread, Darwin could explain the

origin of closely related yet geographically mutually exclusive

"representative" species by asserting that as a species spreads out

over a great area it will meet with different conditions, which stimulate local

adaptations. He could also differentiate between genera that were small because

of extinction among the ranks and genera that were small because they were at

the start of their "life" by determining whether there were

"discrete" or "close" species in them. The latter implied a

"new" genus that was varying and producing more species, while the

former indicated an "old" one that was gradually dying out through

the extinction of first one and then another of its species, so rendering the

existing forms rather distinct from one another. Furthermore, the same argument

was applied to explain why some organisms were rare and others abundant,

although here Darwin conceded that there were many additional factors which

allowed, say, a plethora of individuals to be found in small (and supposedly

"old") genera such as the earwig and platypus. Equally, he could

explain the origin of markedly disjunct species by supposing them to be

"remnants" left behind when a large and correspondingly widely spread

genus died out. 65-6

·

Darwin tried to explain this

idea [variation leading to accumulation of adaptations therefore forming new

species] by relating the quality of adaptation to some physical attribute that

genera might possess, such as the capacity to range widely over diverse

terrains 66

·

By 1855-6 e, the introduction

of a new and good adaptation to a satellite species at the edge of a large

geographical range would lead to the formation of a new line of development

and, ultimately, to the rise of a new genus and the demise of the old.

·

the three main elements of

Darwin's views on divergence in its finished state. First and foremost was, of

course, the notion that life was readily subdivided into different classes,

orders, and families, which indicated a hierarchy of relationships that

evolutionary theory had to explain. Life was for Darwin a branching affair. The

second element of the three which went toward his principle, and the one which has

been noted most often by historians for evident reasons, was the so-called rule

of the division of labor. And the final element of the triptych was that

concerned with large genera and the incidence of varieties, the

"boiler-house" of the whole machine. To it briefly, there was the

phenomenon of divergent lines, the mode by which they were formed, and the cause

and effect attributable to them. Até 1856 eles eram separados

·

O primeiro element sempre

esteve lá, mas até 1854 0 there is no evidence to suggest that Darwin as yet

envisaged a special mechanism for this phenomenon other than natural selection.

He appears to have thought that natural selection would preserve new - and

hence different - modifications that would, in turn, give rise to a cluster of

species and genera that were markedly distinct from the parent form The process

was effected by the geographical scheme described in 1855 and 1856. Darwin

thought that a new genus arose from the introduction of some favorable

adaptation to a satellite species at the edge of the geographical range covered

by any one large genus.. 70-1

·

[sobre o Segundo element] Darwin

was certainly not ignorant of this notion after about 1851 or 1852. But he

tried at first, and especially in 1855 when the idea of a division of labor

appeared often in his notes, to relate this evidently "beneficial"

diversification to a combined cause of competition and the absolute abundance

of resources in any one area. A division of labor was not applied to the

question of divergence of character, for Darwin already had an explanation for

that in peripheral differentiation. It was applied instead to the problem of

accounting for the difference in the amount of life which regions could support

·

In short, although this was

clearly a passage elaborating on the phenomenon of a division of labor and the

diversity of associations, there was here no talk of selection favoring the

most

distinct variety which

might appear. Nor did Darwin at this time put these thoughts about diversity

into a temporal context to illuminate how he saw the branches of the

"tree" of life sprout and grow away from the root stock. Instead, the

division of labor was explained in terms of natural selection and served, in

turn, to explain what we might call the "biomass" of an area. He went

on to argue in the closing sentences of this piece that poor regions encouraged

little interspecific competition and therefore tended to support remarkably

uniform floras and faunas, such as heathlands, conifer forests, or freshwater

biotas. The "fertile meadow," by contrast, supported "more

life," not because this was how God or anyone else had envisaged it, but

because there had been a great deal of "struggle." Hence competition

and the idea of "resources" between themselves accounted for the

"amount of life supported in a given area."

So it appears that the

division of labor, useful as it undoubtedly was, was brought into the embrace

of natural selection theory as it then stood. It did not stimulate a

reconstruction of that theory, as is often assumed to have been the case.

Although introduced into Darwin's thoughts in 1852, it did not then or

subsequently (for a few years at least) mean the same thing as it represented

in the final principle of divergence. It was, we might say, adapted to its

immediate context. 72

·

(terceiro: variação) Although

this was a process of accumulated differentiation or divergence from the

original stock, Darwin did not - before mid-1857 - invoke a principle of

divergence to explain such an action. Instead he believed, as already

indicated, that natural selection alone took care of the process of increasing

divergence from the norm. Natural selection "made" species by picking

out those variations which were well adapted to the prevailing circumstances,

and pushed them on and on in some one direction. Once again, there was no talk

of selection actually favoring the most diverse variety which happened to

appear in any series. 73

·

This addition [OF THE PRINCIPLE

OF DIVERGENCE] was finished in the early summer of 1858 and inserted into

Chapter VI, "On Natural Selection," which had originally been

considered complete on March 31, 1857. The most obvious explanation for this

action is that Darwin was in some way ignorant of - or at least uncertain or

uneasy about - the subject matter of his interpolation 74

·

Without any explanation of

divergence, Darwin did two things. He emphasized the role of competition, and

described the availability of suitable "places" in the "polity

of nature" for every step from varietal to specific rank. Competition for

these "places" insured that only a "well-adapted" variety

succeeded in occupying them, and that one form was always replaced (or rather,

ousted) by another that was even more "well-adapted" or

"better" organized. This process of replacement appeared to move in

or tend toward certain directions, a phenomenon which Darwin had difficulty in

explaining. Here he fell back on the phrase "expression of variation in a

right direction" to indicate - in an unintentionally teleological manner -

such a movement. It was a convenient if cumbersome phrase for the trends which

he was later to call divergence of character. [right deviations could fill

niches in nature] 74-5

·

With a principle of divergence

[] He could state that it was not "niches" or "places" that

determined which variety should survive. The forms which escaped extinction did

so because they were the most different [] Darwin did not have to talk of there

being a readymade number of ecological niches waiting for the newly modified

variants to come along and occupy them. On the contrary, he could claim that

modified forms were so different from those previously in existence that they

automatically created their own "places," where none had been before,

on the rare occasions when they could not simply oust a lesser variant from its

home. Since it was the most extreme variety which survived, the overall

construction of the population would tend to become more diversified and, under

the rule of the division of labor, several lines of modification would be

encouraged. Hence the "amount of life" supported by any one region

would become ever more diverse and complex. In sumrnary then, Darwin's initial

attempt at this sixth chapter (completed March 1857) was focused on the

question of explaining diverging lines of evolution - a "right

direction" - without any idea of a principle which might invoke

selectional advantages for those forms which happened to be most different from

the ancestral stock 76

·

Darwin's idea of

"large" was throughout his earlier statistics in reality simply a

statement of "bigger than." He seemed to have no concept of any

absolute largeness or bigness. Lubbock undoubtedly seized on these

discrepancies and pointed out that Darwin was calculating relative largeness

when his conclusions spoke of some real difference in size. Lubbock therefore

abolished all connotations of relativity and substituted a division of the

given population into two halves, one containing all the truly large genera and

one the small. Now, even if people quibbled with Darwin over his definition of

"large," at least he had defined it in unequivocal terms. The central

question therefore remained the same one that Darwin had posed in earlier

computations: Do varieties (or commonness or wide range) occur in the larger

genera? But it was rephrased by Lubbock to insure that it was rigorously

answered 80

·

Briefly, then, the story line

runs as follows. Despite an early awareness of the phenomenon, Darwin did not

see the need for a principle to explain divergence until some time between

composing the "Essay" and the Origin. The recent publication of

Natural Selection shows that Darwin possessed precisely the same concept of

divergence in the spring of 1858 as he had in 1859, because he added a long

section on this topic to his original Chapter VI, "On Natural

Selection." From internal analysis of the first draft of this chapter,

completed in March 1857, it appears that Darwin did not at this earlier time

have any fixed notion of a "'principle" per se, although he was

trying to account for the same phenomena by using only natural selection.

However, as demonstrated earlier, he did possess all the elements of a

"principle" in his intellectual repertoire, although these too were

correlated with natural selection. Therefore, he did not have the principle in

March 1857, and he did have it in the spring of 1858. We can make a further

refinement of this statement by drawing in the two letters which Darwin wrote

to Hooker and Gray, describing his "principle of divergence" in scant

detail, during the late summer of 1857. These were dated August and September,

respectively.84

·

On July 14 Lubbock introduced

Darwin to a new way of doing his botanical calculations and caused Darwin to

reject all that had gone before as "the grossest blunder."

Momentarily startled and dismayed by this unwelcome revelation, Darwin refused

to relinquish the conclusions which he had come by so conscientiously and

prepared to start again. The changes which Lubbock encouraged him to make

forced him to look not at the relative size of genera but at the absolute

"bigness" or "smallness" that each presented. He had

formerly been content to put forward results where "large" was merely

a question of being bigger than the standard - as four was bigger than two -

and so he called any genus large as long as it possessed more species than the

control. Now, however, in July, Lubbock made him contrast absolutely large

genera of a predetermined size with correspondingly small ones. This change in

emphasis made Darwin shift his gaze to focus on the success which large genera

so evidently enjoyed. He suddenly saw that it was not just variation and the

fortuitous production of "good" adaptations which induced large

genera to produce yet more and more species, but it was also their potency.

Large genera really were more successful than the small. They were, in fact,

the very acme of success, being more widespread and more abundant in

individuals than their smaller confreres, and also turning out more varieties

within which more "good" adaptations were likely to emerge. Large

genera were the winners, and their size was a definite statement about their

superior position in life. In a biblical turn of phrase, Darwin asserted that "in

the great scheme of nature, to that which has much, much will be given."

It was this notion of success and its corollary of "winner takes all"

which allowed Darwin to collect and fuse together points that had up till then

been separate entities in his mind. All at once things fell into place. Insofar

as we can decide what may have been going on in anyone's mind, this

reassortment of details can be reconstructed as follows. Through Lubbock's

ministrations, Darwin suddenly recognized that large genera had more advantages

than most. This was why they were widespread and numerous in individuals. Where

before he had spoken only of forms being "better" adapted to their

surroundings, here he had real advantages to deal with. The varieties which

were produced in such numbers from the larger genera should also be superior,

if his ideas about the inheritance of characters were true. Moreover, natural

selection told him that "good" variations were preserved, so what

happened to this wealth of superior variants? Here, he invoked the division of

labor, which permitted any number of individuals to coexist as long as they

were more or less distinct from one another. He was therefore confronted with a

vision of many superior variants vying with each other for "places"

in the economy of nature, and with the rule that only the most diversified set

of individuals would manage to live together; from this state of affairs he

could ascend easily to the proposal that it was the most distinct or extreme

variety which was favored by natural selection. Once he had an association

between the notions of "advantage" (that is, success) and

"diversification," everything else followed. If selection was tending

to push varieties away from one another in morphological or behavioral terms,

then it must also be forcing species to develop along lines of modification

that diverged from one another. Darwin could now quite clearly see that a large

genus would eventually fragment into several smaller groups of species by a

splitting action, and not from the pronounced superiority of a single species

which then eliminated its congeners. A large genus broke into two or three sets

of species, each one of which was characterized by a markedly distinct

modification. But in the course of time, as he must have been aware, this

sequence of growth, splitting, and growth would gradually add to the number of

genera on the earth unless there was some extinction going on. The power of

extinction was thus called in to maintain a semblance of balance in the history

of living beings, and he reasoned that forms which were not sufficiently

extreme or different must fail to reproduce their kind. Hence, by a circuitous

route, Darwin arrived back at the same proposition with which he had started:

that it was the most distinct form of life that was favored by natural

selection. Such a revisitation may have reinforced the truth of this maxim in

his own mind, for had he not reached exactly the same point from two directions

- the preservation of "good" varieties and the elimination of the

"bad"? 84-86

·

Under this interpretation of

Darwin's work before the Origin, the emergence of a principle of divergence can

be seen as the last leg of a long inquiry into the general issue of divergent

evolution. Over this period Darwin approached the question from a number of

angles: at times he thought the problem was solved; at others it ballooned out

in a disturbing and temporarily uncontrollable fashion, forcing him to

reevaluate previous arguments, to gather new information or reinterpret the

old, and to provide reformulated explanations. It was a see-saw existence. Many

of the phenomena of divergent evolution noted by Darwin through the years

1837-1840 found an explanation in the sketches of 1842 and 1844. Having dealt

with these facts to the best of his ability, Darwin turned to a study of

barnacles, no doubt to corroborate his writings in various ways. There, a whole

new range of evidence was disclosed, obliging him to return to the thesis of

1844 in order to expand and alter his lines of reasoning. Divergent evolution

surfaced as one of the more significant difficulties in need of a solution. In

the immediate postbarnacle years he may well have explained divergence through

using the concept of a division of labor, as many historians believe. But the

issue was not closed. In the light of unlimited variation in nature Darwin

undertook numerical studies of varieties, species, and genera, to determine the

"source" of new species. Over a period of months (from 1854 to the

end of 1856) this botanical arithmetic indicated that large genera were more

"fertile" than the small. Darwin, never one to leave a fact

unexplained or a question unasked, noted that if a "fertile" genus

produces more and more species, these species will merely remain variations on

a single theme unless divergence intervenes. How could the genus split into

several genera? At first, before the beginning of 1857, he answered this

question with a somewhat hazily formulated scheme of geographical isolation,

depending for the most part on results drawn from his arithmetical calculations

bearing on the wide geographical areas covered by species-rich and variable

genera. Yet when he came to order these thoughts into a written synopsis for

the "big species book," then firmly under way, the argument failed

him. The "expression of variation in a right direction" still lacked

an adequate explanation. As he was endlessly turning the problem over during

the first six months of 1857, a relatively trivial event, not immediately

concerned with divergence although intimately connected with his numerical

studies, caused Darwin to stop in his tracks. The reorganization of his

arithmetic stimulated a reorganization of the issue of divergence. The various

pieces of the puzzle were reassociated and reassembled in mid-1857, producing

the much-vaunted "'principle." Its explanatory power was great and

Darwin was eager to provide proper substantiation; he delayed the revision of

the long manuscript until the arithmetical basis of the concept was fully

examined, and then hurriedly wrote up his ideas. The "principle of

divergence" was emphatically part of Darwin's theory by early 1858. 88-89

·

If there is any message from

this sequence of events, it is that Darwin's theories changed and evolved as he

himself grew older and more mature, and that the "Essay" and Natural

Selection - and indeed, the Origin as well - represent only his considered

opinion on the problem of species at a given point in time. There is no good

reason to believe that Darwin's ideas were static from the "Essay"

onward, and no good reason to reject the possibility that the meaning of

certain key concepts changed and developed during the following years 89

Comentários

Postar um comentário