MENDEL

EXPERIMENTS ON PLANT HYBRIDS [VERSUCHE ÜBER PFLANZEN-HYBRIDEN] - MENDEL, 1866.

[Não colocarei as notas dos tradutores aqui, mas elas são muito interessantes]

1. Introdução

Mendel buscava estudar hibridação, o desenvolvimento dos híbridos e seus descendentes.

Predecessores: Kölreuter, Gärtner; Herbert; Lecoq; Wichura... Mas ninguém estabeleceu uma lei para a formação e desenvolvimento dos hibridos, pois é uma tarefa muito complicada. Os experimentos conduzidos até agora permitem determinar a quantidade de formas diferenters que os híbridos apresentam e que seria possível fazer uma separação geracional para determinar suas proporções numéricas ("it does indeed take quite some courage to undertake such a far-reaching task" 4). Oito anos de experimento.

2. Seleção das plantas

Todo experimento depende de seus materiais e técnicas, assim as plantas devem: 1) possuir traços constantemente distintos; 2) Os híbridos devem ser facilmente protegidos de outros poléns; 3) Híbridos e seus descendentes não podem diminuir sua fertilidade. Experimentos foram conduzidos com leguminosas e a Pisum foi escolhida.

Descreve as condições do experimento. 34 variedade testadas, das quais 22 foram escolhidas [buscava plantas puras]. Embora seja difícil determinar morfologicamente, a maioria é considerada P. sativum ou como outras espécies do mesmo gênero. É tão difícil distinguir híbridos de variedades quanto variedades de espécies. [NT: Mendel is using a species criterion here that has become uncommon today and according to which species may be distinguished by differences with respect to a single trait, as long as that difference is exhibited under “entirely identical circumstances”]

3. Montagem e ordem dos experimentos.

Quando duas plantas com características distintas são cruzadas, os traços comuns a ambas seguem com os híbridos e seus descendentes. Caracs diferentes se unem formando uma nova carac que pode ser modificada depois. O objetivo foi observar essas mudanças em duas caracs e investigar a lei que determina como eles aparecem em cada geração.

Diferenças: tamanho e cor do caule; tamanho e forma das folhas; posição, cor e tamaho das flores; tamanho do pedúnculo; tamanho, cor, forma das vagens; tamanho e forma das sementes e cor das sementes. Mas alguns deles não são caracs discretas. No final deveria se saber se as caracs selecionadas seguem um comportamento [segregação] igual no híbrido e se é possível saber a partir disso sobre as caracs subordinadas. Escolheu-se: forma das sementes (lisa/enrugada); cor do endosperma (amarelo pastel, amarelo claro, laranja, verde intenso); cor do "coat" da semente (bem complexo); forma da vagem (lisa/enrugada); cor da vagem não madura (verde/amarelo); posição das flores (distribuídas ao longo ou concentradas no final do caule); tamanho do caule (longo/curto).

Apenas as mais saudáveis foram seleciondas de cada cruzamento. Plantas não saudáveis não dão flor ou geram sementes que não germinam. Cruzamentos recíprocos foram feitos. Um controle foi feito para evitar a contaminação por insetos. Contaminação pode ocorrer se a flor não se densenvolve corretamente. Mendel assegura que o perigo de contaminação é negligenciável em Pisum.

4. A conformação dos híbridos

Não é uma lei que os híbridos sejam intermediários a seus pais. Isso ocorre com algumas caracs apenas. Em outros casos, caracs de um dos pais são transmitidos sem modificação e suplantam completamente os do outro. Chamaremos eles de recessivos (chamados assim, pois ficam inobserváveis em uma geração, mas podem reaparecer na próxima) e dominantes. As caracs são independentes do sexo da planta.

Lista quais são as caracs dominantes das observadas. Os caules tendem a ser mais longos que o dos pais e as coats mais pintadas.

5. A primeira geração de Híbridos.

Razão de 3:1 entre dominantes e recessivos. Foram feitos experimentos para cada par de caracs. Não foram observadas formas transicionais.

Tem um certo grau de indeterminação e continuidade dos caracs. mas é bem explicada.

O carac dominante pode significar uma carac parental ou do híbrido. Só é possível determinar isso na próxima geração [F2], se for parental o carac será transmitido a todos os descendentes sem modificação, se for híbrido será segregado. Para Mendel o híbrido não representa um estado orgânico resultante da mistura de duas espécies e perpetuado para a prole, ser híbrido não é necessáriamente herdado pela prole.

6. A segunda geração de híbridos.

As formas recessivas quando cruzadas com si mesmas não mais variam. Das dominantes, um terço continua invariante, e os outros dois se comporta como a primeira geração (3:1), resulta um proporção de 2:1 entre híbridos e plantas puras entre as dominantes " 16. Nos experimentos onde isso não se confirma o N amostral é muito baixo. Assim, híbridos com dois caracs diferentes dão sementes das quais metade geram a forma híbrida e a outra metade continua pura entre recessiva e dominante.

It is thus proven that, of those forms that possess the dominating trait in the first generation, two parts carry the hybrid character, whilst one part remains constant with the dominating trait. The proportion of 3 : 1 according to which the distribution of the dominating and recessive characteristic occurs in the first generation, thus resolves itself into the proportion 2 : 1 : 1 in all experiments, if one all along distinguishes the dominating trait in its meaning as a hybrid trait and as a parental characteristic. 16

7. A próxima geração de híbridos.

Os experimentos seguiram sem grandes desvios por várias gerações. A é adotado para representar o carac dominante e a para o recessivo, levando a: A + 2Aa + a.

Reversão também é contemplada.

Assumindo que as plantas tenham a mesma fertilidade, metade das sementes darão origem a plantas puras e a outra a híbridos, ao longo das gerações os híbridos permanecem iguais proporcionalmente.

8. Os descendentes dos híbridos com múltplos caracs.

Os híbridos sempre se aproximam mais do pai com a maior quantidade de caracs dominantes. Se um dos pais só tem caracterísicas dominantes então o híbrido se distingue pouco ou nada.

Cruzando AaBb (obtidas por cruzamento entre AB [AABB] e ab [aabb]) entre si temos 1) grupo AB, Ab, aB e ab que são constantes; 2) ABb, aBb, AaB e Aab constantes em um carat. e hibridas no outro no qual variam na próxima geração; 3) AaBb, híbrido em ambos os traços e se comporta como seus progenitores quando cruzado. Proporção 1:2:4.

AB+Ab+aB+ab+2ABb+2aBb+2AaB+2Aab+4AaBb

Uma junção [combination series] de;

A+2Aa+a

B+2Bb+b

Faz mais um experimento com três caracs chegando a 1:2:4:8.

Os descendentes dos hibridos multicaracs. representam uma junção de duas séries simples. Ainda, o comportamento (segregação) deles é independente.

Se n for a quantidade diferenças entre as duas plantas parentais, 3^n é o número de membros na junção; 4^n o número de indíviduos; e 2n o número de conjunções que é constante. Assim, caracs constantes que ocorrem nas várias formas das plantas aparecem em todas as combinações possíveis pelas leis de combinação ao realizarmos repetidas fecundações artificiais.

Faltam experimentos quanto ao tempo de floração.

Sumariza, dizendo que há um comportamento completamente concordante em união híbrida:

The descendants of hybrids of two respective differing traits are hybrids again in one half, while the other half becomes constant in equal portions with the characteristic of the seed and pollen plant. If several differing traits are united through fertilisation in a hybrid, then the descendants of the same form members of a combination series in which the developmental series for each of the two differing traits are united. 24

Supõe ainda que as mesmas regras devem se aplicar aos caracs. não tão discretos, como atesta um de deus experimentos (entretando fica difícil categorizar os resultados).

9. As células de fertilização dos híbridos.

Formas constantes ocorrem entre os descendentes do híbridos em todas aas combinações de caracs. unidos. Formas constantes só podem ser formadas se os gametas forem do mesmo tipo com a mesma disposição de animar indíviduos idênticos como ocorre com autofecundação de espécies puras. Assim, é necessário que na geração das formas constantes a partir dos híbridos fatores [caracs, NT: Mendel is taking over Gärtner’s terminology here who addressed the two parties in hybridisation as “Faktoren”. As Robert C. Olby has emphasized, Gärtner used the term to refer to the species hybridized, rather than underlying dispositions for particular traits] idênticos agem juntos.

Uma planta pode gerar diferentes sementes, com diferentes constituições, muitos tipos de gametas podem ser formadas relativas a seus produtores favorecendo vários tipos de combinação inclusive constantes. [NT: Mendel refers back here to his observation that segregation of seed traits can be observed in one and the same pod; see p. 19, s. 8. He is again deducing a hypothesis to be tested by the back-crosses he reports on in this section. The sentence formulates an important analogy between macroscopic “forms” and the microscopic “constitution” of gametes, which is restated at the very end of Section 9. It is important to keep in mind that “forms” here, as elsewhere in Mendel’s paper, does not only refer to visible traits, but to transmission behaviour as well, in this case the “constancy” of traits in transmission. “Constant forms” have the status of species for Mendel]

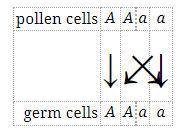

Segundo mendel, isso explica como a formação de híbridos a cada geração é possível se for admitido que cada espécie de gameta é formada na mesma proporção no híbrido. Após vários experimentos ele conclui que os híbridos formam gametas qeu correspondem em quantidade igual a todas as formas constantes que emergem da combinação dos caracs unidos na fertilização. Exemplo:

A+2Aa+a

Gametas

Masculino A+A+a+a

Feminino A+A+a+a

Recombinação

Until now, hardly anything more is known with certainty than that flower colour is an extremely variable trait in most ornamental plants. The opinion has often been expressed that the stability of species is either upset to a high degree or entirely broken by cultivation, and there is a strong inclination to present the development of cultivated forms as irregular and accidental; in this context, the colouration of ornamental plants is usually pointed out as the model of all inconstancy. It is not understandable, however, why the simple transfer of plants to a garden plot should result in such a thorough and sustained revolution in the plant organism. No one will seriously want to maintain that plant development in the open country is guided by other laws than on the garden bed. Here, as there, typical modifications must appear once the conditions of life are changed for a species and this species possesses the capacity to adapt to the new circumstances. It will gladly be acknowledged that the origin of new varieties is favoured by cultivation and that by the human hand many a modification is sustained that would succumb in a free state, yet nothing entitles us to assume that the tendency to form varieties is so extraordinarily increased that the species lose all autonomy and their progeny diverge into an endless array of highly variable forms. If the change in conditions of vegetation were the only cause of variability, then one might expect that those cultivated plants which have been grown under almost identical conditions for centuries would have regained some of their autonomy. This, however, is not the case, as we know, because it is precisely among these forms that not only the most diverse, but also the most variable forms are found. Only the Leguminosae like Pisum, Phaseolus, Lens, whose fertilisation organs are protected by the keel, provide a noteworthy exception from this. Even in this case, numerous varieties have originated under multifarious conditions in over 1000 years of cultivation[;] these maintain, however, the same autonomy under constant conditions of life, as the one that characterises wild growing species. 36-7

Maravilha, Pedro! Você tem que arrumar um tempinho para compartilhar esse conteúdo com a gente. Na semana passada estávamos justamente falando do Mendel por conta das nossas leituras de Jacob.

ResponderExcluir